3 Questions with Antonio Mussa: Cyclones, COVID-19, and Antimalarial Interventions

June 11, 2020 | 4 Minute ReadDisruptive events like COVID-19 and natural disasters take the spotlight away from other harmful diseases like malaria. Antonio Mussa explores parallels from these events in Mozambique.

Devastating cyclones and global pandemics like COVID-19 can distract Mozambicans from addressing the pervasive problem of malaria, which is often seen as a part of daily life even though it is responsible for 29 percent of all deaths in the country. As COVID-19 spreads through Mozambique’s northern provinces, Antonio Mussa, chief of party of the Chemonics-led USAID Integrated Malaria Program (IMaP), is already applying lessons learned from the disruptions caused by cyclones to antimalarial interventions that left communities vulnerable a little over a year ago. We asked Antonio about lessons learned from IMaP’s response to Cyclones Idai and Kenneth in Mozambique:

How did the project address the immediate and long-term challenges that IMaP faced in terms of disruptions to antimalarial interventions and health services provided by the government when the cyclones hit the northern provinces and as Mozambique faced COVID-19?

The immediate challenge was not being able to physically reach health facilities to provide technical assistance due to roadblocks. As the heavy rains and floods wiped off most of the roads and displaced communities, Mozambique was not prepared to cope with an emergency of this scale. Making matters worse, a cholera outbreak also erupted after the cyclones’ devastation, which led to people forgetting what they learned about malaria and focusing only on their more immediate needs.

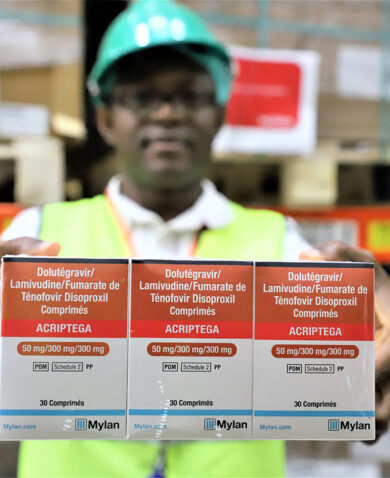

We overcame these challenges by establishing regular coordination meetings with the government, particularly with the Provincial Department of Health (DPS), and other local partners, leveraging a forum of implementing partners to design a communications strategy to spread the message on malaria prevention. We also assessed the number of healthcare workers who were not updated in malaria management and supported the government to address this gap. In Cabo Delgado province, which took a direct hit from Cyclone Kenneth, we provided services to the displaced communities near the provincial capital, Pemba. While local provincial government’s focus was on addressing the cholera outbreak, we worked with them to combine malaria prevention messaging alongside messages on WASH to prevent diarrhea caused by cholera. In the Pemba periphery and in coordination with implementing partners, we trained 27 participants on malaria prevention strategies, messaging, and treatment while using health facilities to deliver goods to treat malaria. And for the health facilities we couldn’t reach, we relied on community leaders and community health workers to spread malaria preventive messages, promote rapid diagnoses, and deliver immediate treatment.

As Mozambique faces COVID-19, something similar is happening, and people are starting to deprioritize malaria once again. The global pandemic is also disproportionally affecting the province of Cabo Delgado, which is one of IMaP’s areas of intervention and the furthest away from the country’s capital, Maputo. With IMaP being the lead partner for antimalarial interventions in the provincial level, we immediately called the forum to coordinate activities to leverage the available synergies we established after the cyclones. Having already tested our capacity to cope with disruptions after Cyclone Kenneth has given us a head start to cope with this new crisis.

What were some of the activities that IMaP helped plan in the communities to prevent malaria in the aftermath of the cyclones in 2019?

At the community level, we used explainer videos to illustrate how to maintain good antimalarial habits during emergencies. We paired the videos with a messaging campaign and activities to influence social behavior and took advantage of the community outreach efforts to deliver supplies. In Pemba, we provided case management training to health workers that were not initially trained on antimalarial intervention strategies and supported 121 health care providers. In terms of the aftermath activities, one of the main constraints was that most of the health facility infrastructure was damaged. While IMaP couldn’t support directly rebuilding these facilities, the project was able to support the distribution of tents to temporarily replace health facility infrastructure.

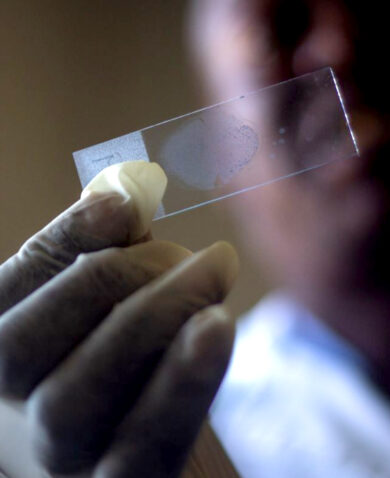

In terms of coordination with our partners, we actively combatted the effects of the cyclones’ aftermath by participating in daily meetings with the DPS to get updates on the number of people displaced and the number of people with malaria and diarrhea. We coordinated with the government to get rapid diagnostic testing to where it was needed and used DPS’s mobile clinic to reach affected communities and remind the population about the continuing risk of getting malaria.

What lessons learned from the disruptions caused by natural disasters that can be applied to the disruptions caused by COVID-19?

The tendency in any new emergency is to focus the attention to that situation and forget the previous crisis. With COVID-19, we must constantly remind communities that malaria is still out there and that there are ways to get diagnosed and treated. Community radio is a good tool to spread this message in rural communities. Even though IMaP’s focus is on antimalarial interventions, we are also providing services to the DPS to spread the message on COVID-19 and using this chance to spread our antimalarial message.

One of the lessons learned is to take the opportunity to focus on the project and on building partnerships. Coordination is crucial. Having all the partners aligned creates opportunities for synergies and prevents redundancies in interventions, especially at the community level. While IMaP is not designed to combat COVID-19, we are informing the national government about the reality of the pandemic on the ground and raising awareness in the Ministry of Health, thus bringing support to Cabo Delgado to face COVID-19 and malaria. To avoid disruptions to our antimalarial interventions, we quickly re-established coordination meetings, and we have the resources ready to provide support to entities at provincial and national levels to help combat malaria. One of the key activities is communication, and if you spread the messages to the communities, we can prevent malaria and use the same channels to spread COVID-19 messaging.

*Banner image caption: Long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLIN) distribution in Mozambique. Photo credit: Mickael Breard

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.