Climate Information Services: Distilling Data into Informed Decision-Making

March 14, 2017 | 4 Minute ReadSatellites are producing more data through remote sensing and earth observation, but will people use it?

Climate information services (CIS) is the new acronym on the block in the global environment and climate resilience community. The Global Framework for Climate Services (GFCS) is the leading international advocate and authority on CIS. It was established in 2009 as a result of a U.N. initiative to support integrated international efforts for the development and uptake of CIS in support of decision-making. GFCS emphasizes that “climate is what you expect, and weather is what you get,” and defines CIS as any tools or services that “prepare users for the weather they will actually experience.” Weather services prepare users for the weather they’ll likely experience within days, while CIS prepares users for anticipated weather on seasonal or decadal timeframes.

Although the term CIS and its use in international development are quite nascent, the CIS industry has been around for decades, operating without a formal title. Indeed, the entire aviation sector could not function without CIS to gauge wind speeds and avoid storms. Even if you listen to news reports about next year’s El Niño season, you are using a CIS that will influence your decisions.

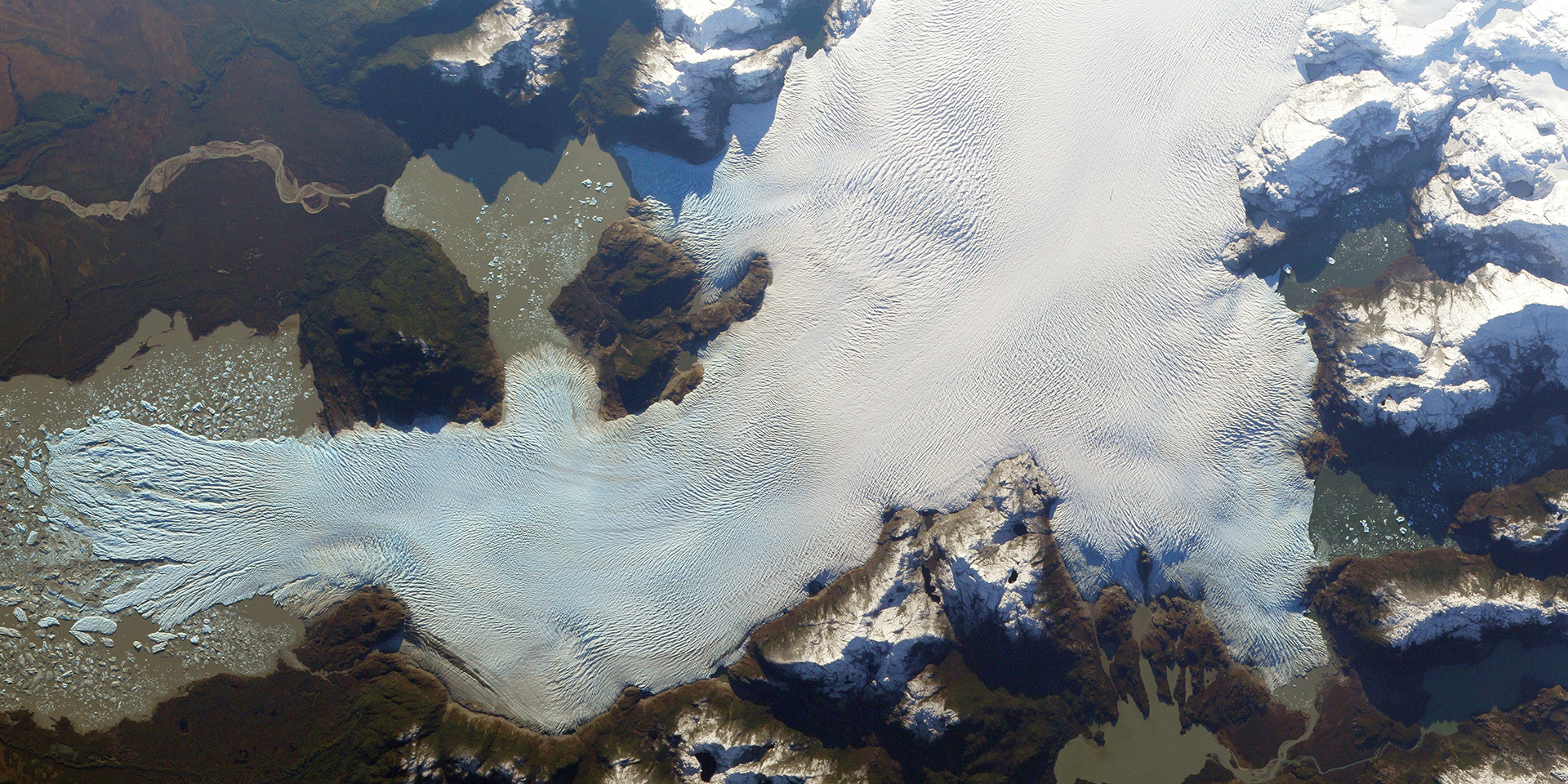

But we are in a new era of CIS that is revolutionizing business as usual, in both the private sector and in international development. This era is characterized by increased public access to climate data, more climate variables with higher resolution data and projections, the presence of condensed and seasonal timelines for climate predictions, and a higher degree of geographic exactness that can account for microclimatic data that may have been previously overlooked.

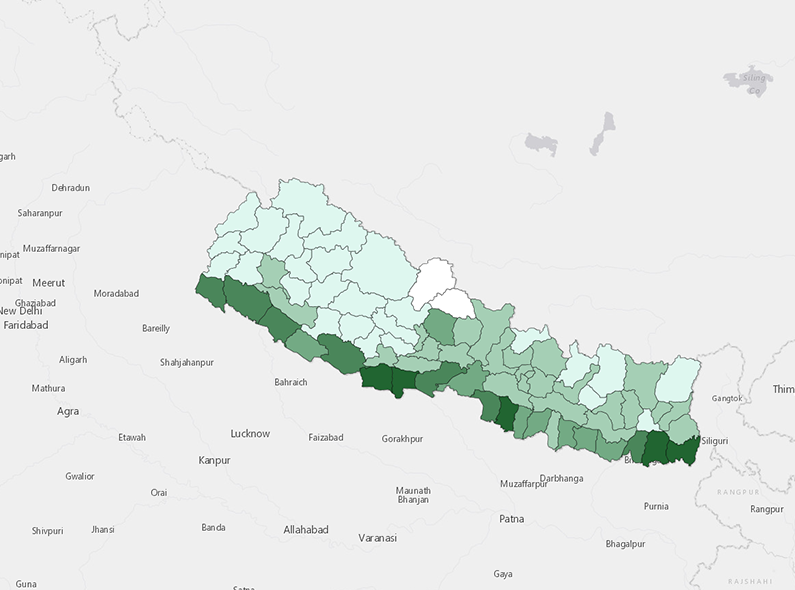

This new era of CIS is a potential game changer for international development. After all, an African subsistence farmer can’t make lifestyle changes by simply knowing that it will be hotter and drier in 50 years. Farmers must know which crops will succeed in the upcoming season, which crops are marketable, which week’s forecast is ideal for planting, and when the perfect time is to harvest a crop. Innovative CIS tools can bridge this gap. When applied on a national or regional scale, a successful CIS tool with measurable uptake by farmers could mean the difference between national growth and famine.

My recent attendance at the Fifth International Conference on Climate Services in Cape Town, South Africa, sponsored by the Climate Services Partnership, revealed that a nuanced approach to CIS development and application is needed for success. Of central importance to the conference discussions was the need to engage more deeply with the end users of CIS to customize CIS products, whether that’s a rural farmer worried about their next harvest or a government official in a city trying to establish land zoning policies. In practice, knowledge and power currently come from the CIS developer, and the tool’s end users are just static recipients on the tail end of the value chain as data is distilled into climate-informed decisions. Can we transform this paradigm so that knowledge and power truly derive from those who will actually use CIS tools? If we can’t, perhaps the Internet will be a graveyard of unused and poorly maintained decision support tools that scientists all agree are cool gadgets and gizmos that could have changed the world.

Although the quest to fully engage with CIS end users is perhaps the most difficult, CIS practitioners face other challenges as well. It’s a new industry with overlapping and inconsistent terms, best practices, and international efforts. More harmonization of efforts is needed. The Climate Services for Resilient Development Partnership seeks to forge this global link for data sharing and knowledge transfer by linking up partners like Google, NASA, NOAA, Esri, USAID, and the American Red Cross. Similar entities like ClimateEurope fill similar regional roles in Europe, drawing in partners like the Climate Service Center Germany (GERICS), Horizon 2020, and the European Space Agency (ESA).

In the developing world, climate data can be scarce to the point of insufficiency and this dearth of data makes it difficult to produce accurate climate models. The little data that does exist may have proprietary barriers to access, and the owners of this data may have limited capacity to fully capitalize on this information in a meaningful way. The German government-funded West African Science Service Centre on Climate Change and Adapted Land Use (WASCAL) and Southern African Science Service Centre for Climate Change and Adaptive Land Management (SASSCAL) projects support improved data access in Western and Southern Africa. Not all climate data can come from satellites, so projects like SASSCAL install automated weather stations on the ground to collect the data needed to produce more accurate climate models. And as every CIS project funded by USAID, the U.K. Department for International Development (DFID), and Germany’s development agency (GIZ) pointed out during the conference, there is a massive and continued need for investments in capacity building of local stakeholders to institutionalize and fully harness the power of CIS products. All of these activities need to occur within the context of cross-sectoral integration, as CIS tools must be tailored to infrastructure development, water resources, energy, agriculture, and health sector applications.

We must set the bar for success high, as there is much to be gained from CIS, and the cost of not adapting to climate change is high. If the blossoming CIS industry is ever to achieve its full potential, we must recognize that CIS products can’t be forced on people. When our CIS products are easily accessible, understood, and deemed meaningful by users, people will demand them without provocation. If after all of this is achieved, we still don’t feel a truly momentous demand for CIS products, perhaps we can be humble enough to start again and ask people what they actually want.